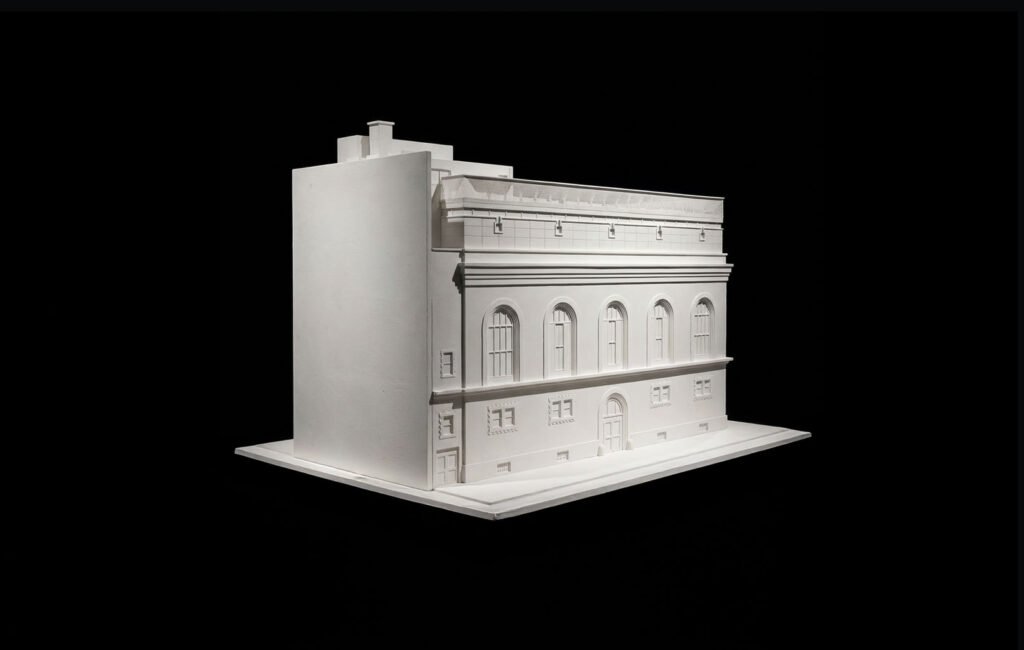

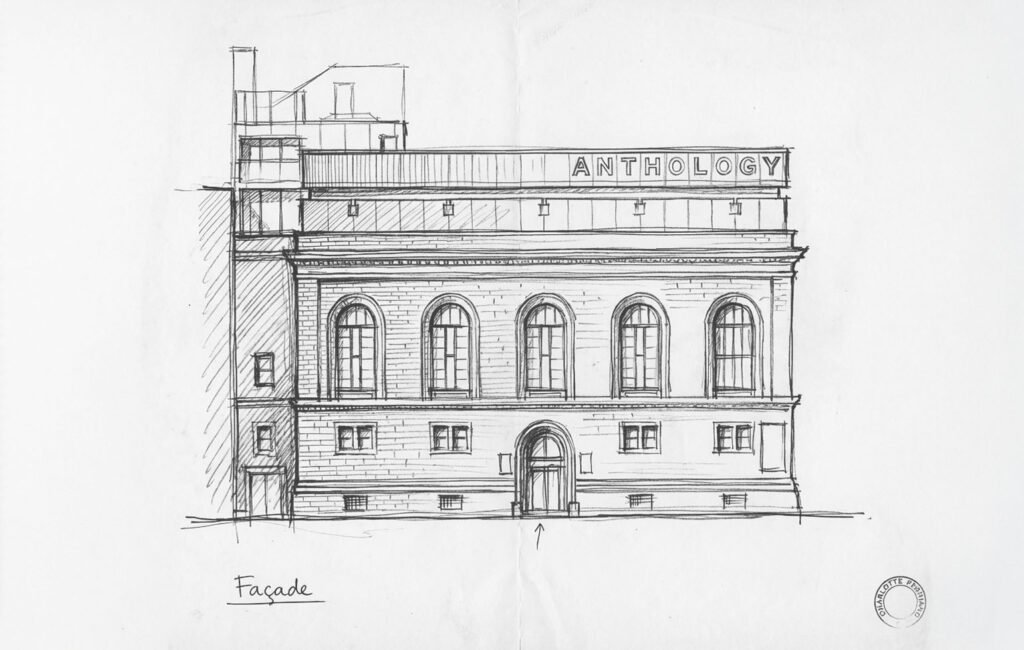

NEW YORK—On the corner of Second Avenue and East 2nd Street stands a building with round arched windows, brick hood molding, and bars over the glass. For thirty-seven years, it has been a home for preserving the art of cinema, showcasing films to audiences seeking something stranger, more experimental, and as provoking as the city around them. This is Anthology Film Archives.

Founded in 1970 based on a vision by filmmaker and poet Jonas Mekas, Anthology was conceived as a permanent, non-commercial space for showing and preserving avant-garde and independent films overlooked by Hollywood. Decades later, Anthology has grown far beyond that founding concept. Today it remains one of New York’s only true film archives, a nonprofit recognized not just for exhibiting films, but for upholding the spirit cinephiles have guarded for generations.

Anthology now houses roughly twenty thousand films, along with recordings, journals, photographs, and ephemera, all...

Keep reading, quickly sign in.

SAVE ARTICLES, ACCESS FULL ARCHIVES, MEMBER PROFILES

NEW YORK—On the corner of Second Avenue and East 2nd Street stands a building with round arched windows, brick hood molding, and bars over the glass. For thirty-seven years, it has been a home for preserving the art of cinema, showcasing films to audiences seeking something stranger, more experimental, and as provoking as the city around them. This is Anthology Film Archives.

Founded in 1970 based on a vision by filmmaker and poet Jonas Mekas, Anthology was conceived as a permanent, non-commercial space for showing and preserving avant-garde and independent films overlooked by Hollywood. Decades later, Anthology has grown far beyond that founding concept. Today it remains one of New York’s only true film archives, a nonprofit recognized not just for exhibiting films, but for upholding the spirit cinephiles have guarded for generations.

Anthology now houses roughly twenty thousand films, along with recordings, journals, photographs, and ephemera, all while operating on a modest annual budget. For years, the organization has quietly pursued a long-planned renovation, one needed to match its programming ambitions while modernizing its infrastructure.

Guiding the project is architect Kevin Bone, who has been intertwined with Anthology nearly as long as the building itself. Originally constructed in 1919 as a courthouse, the structure underwent a decade-long transformation beginning in 1979 when Anthology acquired the property, led by Bone and architect Raimund Abraham.

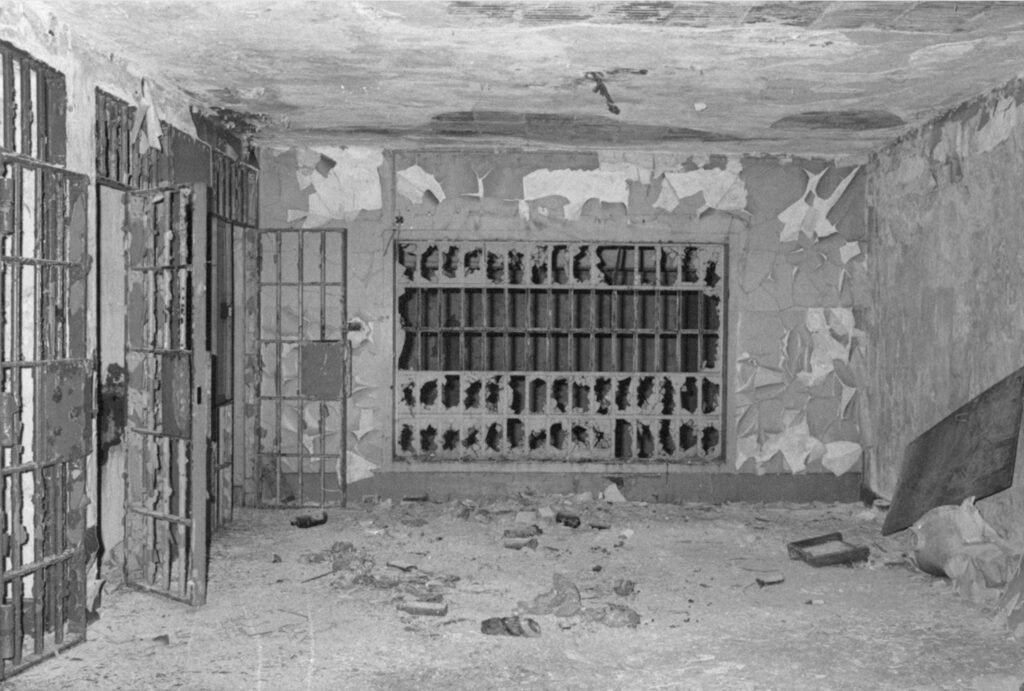

The building’s genetics, from its interlocking staircases that separated prisoners from judges, to barred windows, continue to shape every design decision. In conversation with Bone, a renovation philosophy emerged that is rooted in Anthology’s identity. Together with John Mhiripiri, Anthology’s longtime executive director, Bone emphasized that unlike other trend-driven venues, Anthology’s mandate is preservation.

Preserving a Cinematic History

CLARA MACMEEKIN: Can you tell us about some of the history of Anthology Film Archives for those who don’t know?

JOHN MHIRIPIRI (ANTHOLOGY’S DIRECTOR): In 1973, Anthology left the Public Theater, moved into SoHo, to the Fluxus House, which was at 80 Wooster Street, because that’s where George Maciunas lived. And he was, on the one hand, one of the fathers of SoHo, pioneering the whole live-work loft movement of artists at the time. And he’s also one of the primary figures in the Fluxus art movement.

Eventually Anthology bought its current building, which is a 1919 courthouse, from the City. We bought it in ‘79, and we raised money to renovate it and did the renovations over the course of the next nine years. We opened in our current home in 1988.

MHIRIPIRI: The architect was Raimund Abraham, an Austrian architect who taught at Cooper Union and was a close friend of our founder, Jonas Mekas, and our other founder, Peter Kubelka. Then Kevin Bone and his partner, Joe Levine, became the architects of record.

MACMEEKIN: Did the building’s history as a courthouse create challenges?

KEVIN BONE (ARCHITECT): There are two interlocking stairways that come from separating judges from prisoners, since the building also housed a jail. Those scissor stairs were completely confusing during the first renovation. There are also bars on some windows that remain.

BONE: When we opened the doors to start, there was a lot that really was not complete. In a way, we are returning to complete the job we started many years ago.

MACMEEKIN: Do you think of the building itself as a cinematic structure, with light, framing, and rhythm playing a narrative role?

BONE: Yes, absolutely. It was imagined as a home for cinema, and it remains effective. We have two cinemas, one larger and one smaller, serving different programming purposes. There will be no compromise to that. Anthology will continue to be a public place where people can see independent cinema in its original medium, in a dignified environment.

Roof Deck, Ground Floor Café, Public Archives Access

MACMEEKIN: Can you tell us about some of the more exciting changes that are expected?

BONE: Architecturally, the key transformation is a new Second Avenue presence. There will be an entry on Second Avenue, and the lobby will circulate between Second Avenue and Second Street. That gives more lobby space, more breathing room, and possibilities for programming, like a modest café, a small exhibition space, or a pop-up event space.

The lobby more than doubles in square footage with the Second Avenue connection. That is really the essential feature.

There will also be some cosmetic transformation of the building envelope. A marker of this new phase includes a cornice element and a marquee around the parapet. We are finishing the infill windows on Second Street, which were part of the original plan but never completed.

MACMEEKIN: I don’t want to get ahead of myself, but there was something mentioned about activating the roof?

BONE: It’s in discussion and there may be some possibilities like that. I mean, we are designing with circulation to the roof, and that’s important. And we have explored the ideas of a kind of roof-level kiosk for catering and whatnot.

We’re hoping that the project gets some momentum. A lot of people will see that this is for real, and that we can begin to think of becoming a little bit more ambitious in what we aspire to do. But right now we really want to just get the shovels in the ground and get started.

MACMEEKIN: You mentioned earlier that Jonas Mekas had an idea about having a café or social area that never materialized?

BONE: The basic plan is to use a portion of the first-floor lobby space. It will be modest, but it will contribute as a public cultural space.

I recently came across a quote from Wes Jackson, a great American naturalist, who said that if your life’s work can be completed in your lifetime, you are likely not thinking large enough. That applies to Jonas. His vision was that the institution would be complete not just in its collection and governance, but that its home would be secure, stable, and contribute to the culture of independent cinema.

MACMEEKIN: Are there design references for the café?

BONE: We are inspired by small-scale cafés integrated into cultural institutions. The aspiration is a wine and beer license, a place to have a small snack and meet before or after a film.

MHIRIPIRI: One reference is the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna, founded in part by Peter Kubelka, also an Anthology founder. They have a small but intimate café that serves beer and wine, where people gather before and after screenings.

BONE: These places create richer cultural experiences. In a time when movie theaters are disappearing, the ones that remain become more precious. My goal is not to do a small job, but to ensure that Anthology does not perish on our watch. It is simply too important.

The Question of Popcorn

JOHN WHITE: I had mentioned a lot of small theatres that have opened, making cinema feel more precious, like Roxy, Metrograph and A24’s Cherry Lane…

MHIRIPIRI: I believe they are all for-profit. And it’s an important distinction. IFC is also corporate owned, whereas Anthology is very much a non-profit organization. Which puts us in a camp with a really great variety of venues: Film at Lincoln Center, MoMA, and the Museum of the Moving Image.

WHITE: I’ve always liked how MoMA doesn’t have popcorn so you have to focus on the film in this clean environment, but it’s a highly debated subject! It’s a different experience.

MHIRIPIRI: Right. And even when I go to movies that offer treats and popcorn, if I’m getting any or if I’m with someone who gets any, I kind of want to be done with it all before the trailers finish. I would distract myself if I’m eating popcorn.

We all grew up going to movies and doing that. But I like to be more dialed in, you know? We never offer refreshments in our theaters. And if we have a café, it wouldn’t be to serve people things that they can take into the theater. That’s primarily because we’re an archive. We can’t afford to attract mice or critters like that because we have our collections on site.

With A Little Help From Our Friends

WHITE: What’s the timeline and budget for the renovations?

MHIRIPIRI: It’s a huge project for us. Our annual budget is around a million dollars a year. And, putting that into context, we have an archive of 20,000 films, 5,000 videos, a couple thousand audio recordings, and a research library with 10,000 or more books.

The expansion project is going to be at least a $20 million project. So it dwarfs the institution’s annual budget. But we are out of space. We don’t have enough room in our film vault or library.

Whether we’re going to devote space to the archive, and take our administrative offices offsite are fundamental decisions.

WHITE: If there were a café or a rooftop activation, or something similar, would that be financially helpful? Because the neighborhood has been activating in new ways: things like Public Hotel, Win Son Bakery and others popping up across the street…

MHIRIPIRI: Yeah, that income would definitely contribute to our general operating budget. Whether it was Anthology operating a café or if we lease the space to a proper restaurant operator. If we had a rooftop deck, we would definitely rent it out for private events.

In the last year, we had more people come and see movies at Anthology than ever in our history. And when we finish this expansion project and reopen, we definitely want people to come to Anthology, and we’re going to be showing films more often. I don’t know how much the nature of our programming is going to change. Our goal is not to change Anthology’s character in any way, but always to produce the best programming that we can, and to let as many people know about it as possible to come and see movies. It’s what we do.